Smart Cities, Soft Connectivity and people-centered decision making processes

“The sum of our parts

The beat of our hearts

Is louder than words”

PINK FLOYD, Louder than Words

(The Endless River, 2014, Track # 18)

Smart cities and soft connectivity

A very interesting report by the World Economic Forum – ‘The Competitiveness of Cities’, published in August 2014 – corroborates the great importance increasingly attributed to cities as an engine of competitiveness and sustainable growth at present.

The aforementioned report indicates four relevant factors that are key to competitiveness of cities:

- Institutions (governance/decision-making framework),

- Policies and regulation of business environment,

- Hard connectivity (core physical infrastructure).

- Soft connectivity.

This post focuses on the fourth factor, because it encompasses issues topics already dealt with on this blog, such as civic engagement, open government and social innovation.

Furthermore, the report by the World Economic Forum rightly supports the shareable view that ‘while soft and hard connectivity are mutually reinforcing, soft connectivity is also about supporting an open society in the city, which spurs ideas, entrepreneurship, innovation and growth.’

This topic is also high on the EU’s political agenda, as confirmed by the Communication of the European Commission ‘The Urban Dimension of EU policies’ released in July 2014.

In my view, the challenge of building ‘smart cities’ implies not only the search for smarter choices about infrastructures (including e-infrastructures), systems of transportation, and Future Emerging Technologies such as smart grids, but also an increasing awareness about the following points:

- Traditional solutions of economic and social challenges are not working anymore. This is one of the most important factors that underpins the lively debate over social innovation (see Hassan 2014),

- In a real smart city, both technological and social innovation are needed,

- Engaging citizens in participatory decision making processes aimed at addressing new and unsolved social issues is the best way of delivering unpalatable reforms, especially in times of hardship, great economic transformation and increasing uncertainty.

Advantages of people-centered decision making processes

In general, civic engagement and participatory approaches to decision making build on the opinion, that can be widely accepted, that ‘in an increasingly massively multi-stakeholder world, legitimacy and authority are no longer centralised or singular’ (Johar, Addarii 2014, 42).

These processes are certainly neither easy to implement nor always capable of rightly ‘capturing’ real needs and aspirations of the citizens, but they foster some specific advantages, which are at the heart of the process of renewing public governance in order to achieve both a more effective use of public resources and higher levels of democratic representation.

The most important advantages of people-centered decision making processes are:

- they enhance the ‘sense of ownership’ of policies and projects felt by citizens,

- they improve, by leveraging on the greater ‘sense of ownership’, the sustainability of the results over time. Actually, it is widely acknowledged that the more citizens ‘sense of ownership’ there is, the more is their effort to keep up with their commitments, and their good citizenship too. Accordingly, social and economic outcomes are generally higher than those produced by ‘top down’ projects,

- they foster openness and transparency of Institutions and public policies. As a result, they also improve immaterial factors key to sustainable development, such as good citizenship, trust both amongst citizens and between citizens and institutions, generally labelled as ‘social capital’.

To reap these potential advantages of participatory decision making processes, we mainly need:

- Local decision makers (in primis mayors) able to accept and implement new decision making systems truly open to the community (see chapter 3 ‘Cities’ of the report ‘Enabling Social Innovation Ecosystems for Community-Led Territorial Development’, recently published by Fondazione Giacomo Brodolini). In such a way, local decision makers are also able to foster both trust between local stakeholders (citizens, universities, companies, experts, financiers and non-profit organizations) and social cohesion;

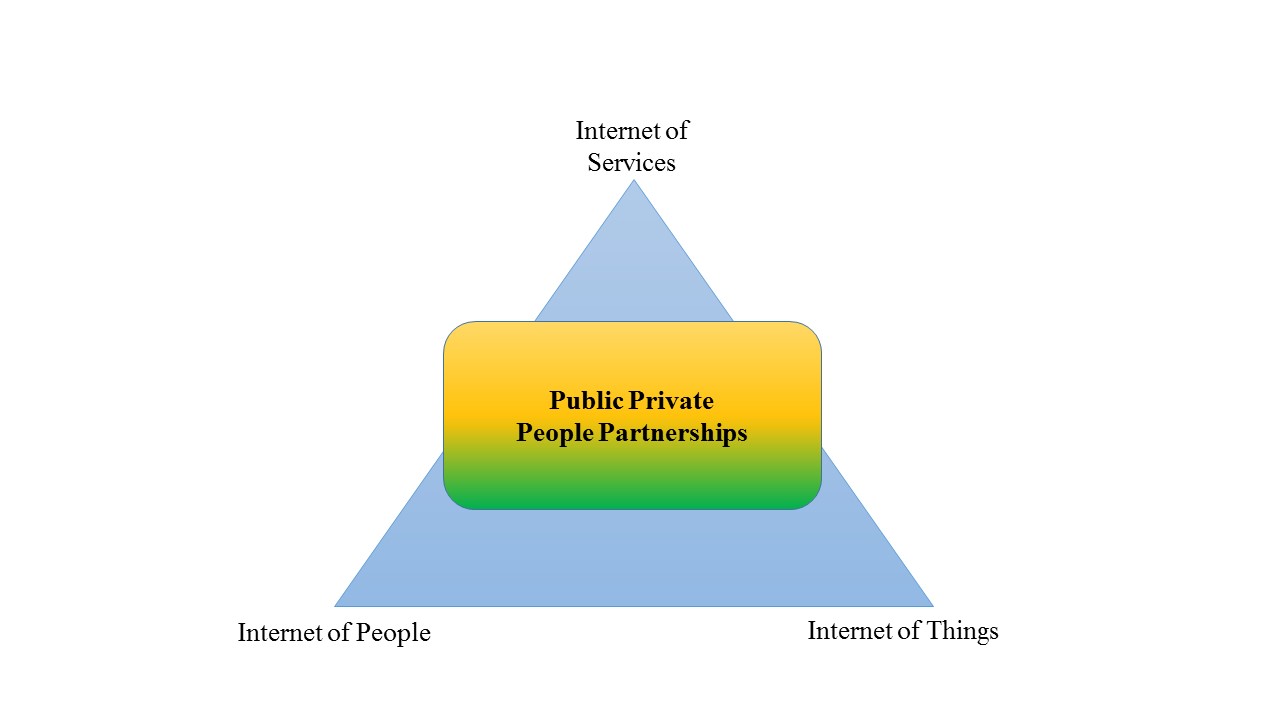

- A wider awareness of how the right combination of Internet of Things, Internet of Services and Internet of People empowers ordinary citizens not only as decision makers, but also as active ‘contributors’, committed to cooperating with Public Authorities in the delivery of social services (see the chart below). For this to happen, we would need reforms that ‘imply a move away from centralised control and regulation towards decentralised, non-regulatory approaches and a stronger emphasis on the role for businesses, civil society and citizens in providing public services’ (Christiansen, Bunt 2012, 9).

Chart 1 – Public Private People Partnerships

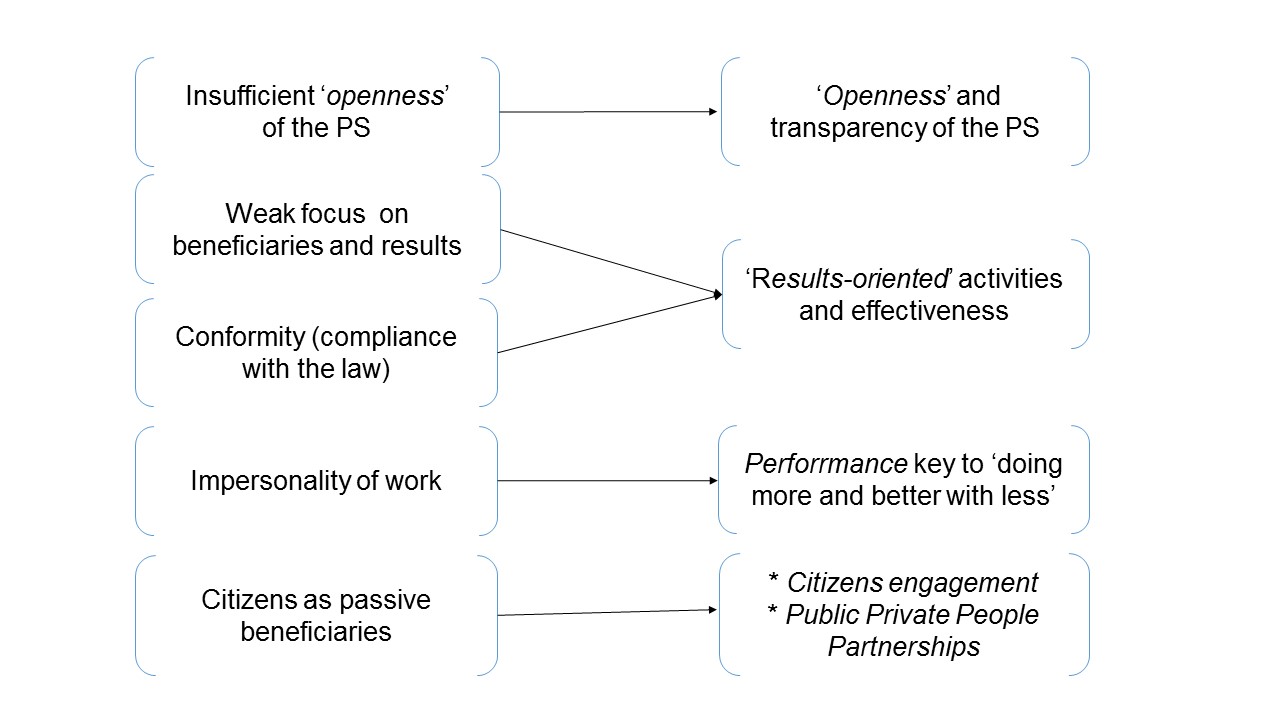

- A bold and wide re-organisation of the Public Administration informed on increasingly accepted concepts, summarized in the chart below. This new guiding principles of public management (open data, citizens engagement and co-design and co-delivery of public services) are extensively treated both in theoretical studies (Dunleavy et al. 2005, Huerta Melchor O. 2008; Eggers, O’Leary 2009, Bason 2011, Christiansen, Bunt 2012, Margetts, Dunleavy 2013, Johar, Addarii 2014) and official documents (European Commission 2012, European Commission 2013a, 2013b).

Chart 2 – Cultural transformation in public government

References

BASON C. (2011), Leading public sector innovation: co-creating for a better society. Policy Press Bristol

CHRISTIANSEN J., BUNT L. (2012), Innovation in Policy: Allowing for Creativity, Social Complexity and Uncertainty in Public Governance, MINDLAB – NESTA, Copenaghen, London

DUNLEAVY P. ET AL. (2005), ‘New Public Management is dead: Long Live Digital Era Governance’; Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, September.

EGGERS W.D., O’LEARY J. (2009), If we can put a man on the moon: getting big things done in government, Harvard University Press, Cambridge (MA)

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2012), Trends and Challenges in Public Sector Innovation in Europe, Brussels

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2013a), A vison for public services, Public Services Unit in DG CONNECT, Brussels

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2013b), Powering European Public Sector Innovation: towards A New Architecture – Report of the Expert Group on Public Sector Innovation, Luxembourg

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2014), The Urban Dimension of EU policies – Key Features of an EU Urban Agenda’, COM(2014) 490 final, Brussels 18.07.2014

HASSAN Z. (2014), The Social Labs Revolution: A New Approach to Solving Our Most Complex Challenges, available at http://social-labs.org

HUERTA MELCHOR O. (2008), ‘Managing Change in OECD Governments: An Introductory Framework’, OECDWorking Papers on Public Governance, No. 12, OECD Publishing

JOHAR I., ADDARII F. (2014), ‘Governing the 21st Century: Reinventing Governance for a Successful Europe’ in SGARAGLI F., eds., Enabling Social Innovation Ecosystems for Community-Led Territorial Development, Quaderno n. 49, Fondazione Giacomo Brodolini, Rome

MARGETTS H., DUNLEAVY P. (2013), The second wave of digital era governance: a quasi paradigm for government on the web, available at http://www.ditchley.co.uk/assets/media/Phil%20Trans%20R%20Soc%20A-2013-Margetts-.pdf

WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM (2014), The Competitiveness of Cities, Davos